La transformation nartistique du fer remonte à la haute Antiquité (-3 200 à -600 avant J.C )

Les découvertes archéologiques d'Assyrie, de Chaldée et les descriptions des civilisations babyloniennes et égyptiennes en témoignent. Des objets contondants tels des pics de lance, flèches et autres outils tels ciseaux et pinces provenant de ces époques lointaines sont exposés dans nos musées aujourd'hui. La tradition européenne prend naissance avec l'art roman au XIIe siècle.

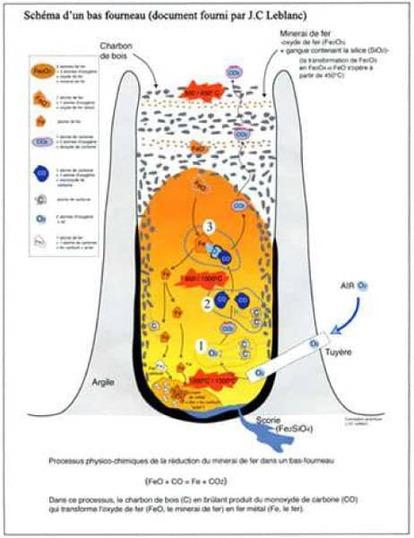

Toutefois, nos connaissances ont bien progressé depuis. La belle aventure du fer a débuté vers l'an 1400 avant J.C. avec l'utilisation de bas fourneaux qui permettait d'obtenir des quantités minimales de fer.

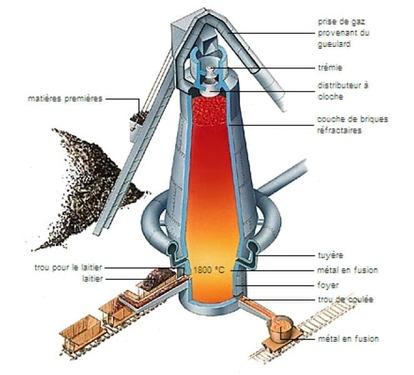

Cette période de la protohistoire, connue comme l'Âge du fer, succède à l'Âge du bronze. Il est intéressant de noter que selon plusieurs auteurs, l'utilisation plus générale du fer se situerait plutôt entre 1200 et 1400 après J.C. avec l'introduction des hauts fourneaux hydrauliques. L'Abbaye cistercienne de Fontenay, construite vers 1220, est unanimement considérée comme un des berceaux de la sidérurgie moderne. D'un point de vue un peu plus concret et écologique, rappelons qu'un peu plus tard, vers 1850, dans la grande forge de Buffon (1707-1788), il était nécessaire de brûler 1500 kg de charbon de bois et de réduire 2700 kg de minerai pour obtenir une gueuse de fer d'environ une tonne.

The ironworker's works are objects and architectural ornaments in wrought iron: gates, balconies, grilles, banisters, furniture or objects of art. Among the small wrought iron works, nails and locks should be mentioned. Among the great works, naval anchors and cannons occupy a special place from a historical point of view. Ironwork has always been the natural decorative complement of buildings in all eras. A certain number of artists distinguished themselves in metal work to meet the demand for public buildings, cathedrals, palaces, prestigious residences of the nobility or the upper bourgeoisie.

However, our knowledge has progressed considerably since then. The great adventure of iron began around the year 1400 BC with the use of low furnaces which made it possible to obtain minimal quantities of iron.

This period of protohistory, known as the Iron Age, succeeds the Bronze Age. It is interesting to note that according to several authors, the more general use of iron would rather be between 1200 and 1400 AD with the introduction of hydraulic blast furnaces. The Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay, built around 1220, is unanimously considered one of the cradles of modern steelmaking. From a slightly more concrete and ecological point of view, let us recall that a little later, around 1850, in the large forge of Buffon (1707-1788), it was necessary to burn 1500 kg of charcoal and reduce 2700 kg of ore to obtain an iron pig of approximately one ton.

En France, de monumentaux ouvrages en fer forgé existent déjà au Moyen-Âge telles les portes ouest de la cathédrale de Notre-Dame-de-Paris. Les Églises au XIIIe siècle étaient de bons clients pour certains articles utilitaires comme les boulons, les pentures et les objets du culte. Sous Louis XIII et surtout sous le règne de Louis XIV, la ferronnerie française atteindra son plus haut niveau d'excellence.

L'Angleterre du XVIIe siècle connaîtra de son côté un fort développement de la ferronnerie à la suite de l'arrivée du ferronnier huguenot Jean Tijou. (1652?-1718?). Il a fui son pays à la suite de la révocation de l'Édit de Nantes en 1685 et gagna la confiance de William III. On lui doit les nombreuses grilles du palais d'Hampton Court. Toujours en Angleterre, Abraham Darby (1678- 1717) met au point un procédé de distillation de la houille (charbon) afin d'obtenir le coke. La découverte de ce combustible performant a été déterminante pour le développement de la ferronnerie et la sauvegarde au XVIIIe siècle des forêts européennes sur-sollicitées pour alimenter les hauts fourneaux.

En Nouvelle-France, Jean-Baptiste Lozeau (1694?-1745?) travaillera comme serrurier et forgeron dans la ville de Québec. Il fabriquera une croix pour le couvent des Ursulines en 1724. Sa réputation était grande puisqu'il fournira deux autres croix : la première pour Chicoutimi en 1726 et l'autre pour Richibouctou en 1732.

Il y a aussi toute une tradition ibérique à souligner. Antoni Gaudi (1852-1926) est la dernière incarnation majeure du fer forgé pour notre époque. Personnalité incontournable de l'Art nouveau, il se plaisait à répéter que : la originalidad consiste en volver al origen (l'originalité consiste à retourner à l'origine).

La pérennité de l'art du fer forgé est assurée car il correspond toujours aux besoins pour lesquels il a été inventé il y a quelques milliers d'années. Chaque époque et chaque style se caractérisent par des motifs qui dépendent des progrès technologiques du moment.

In the 19th century, certain districts adopted a law requiring developers to leave a green space at the front of the building in order to ensure a minimum of greenery for working-class neighborhoods. This law forced developers to build smaller housing at a time when families were very large. Arranging the staircase outside then created a saving of interior space. It is therefore in this context that the exterior staircase was its appearance in the Montreal landscape. But this is not the only reason for using the exterior staircase; the lower heating cost would also be a factor.

It is for its durable and safe side that entrepreneurs of the time favored wrought iron. No wonder foundries specializing in architectural wrought iron experienced such a meteoric rise at the start of the 20th century. Traditionally, black was the color used to paint wrought iron while pale gray was used for balcony floors. These colors harmonized perfectly with the white cornices and moldings of the time.

In the 1980s, the City of Montreal set up incentive programs so that owners would demolish the traditional sheds at the rear of buildings, particularly due to the high fire risks. The wrought iron spiral staircases commonly found at the rear of buildings are the result of these incentive programs. Indeed, several owners have replaced the sheds with these stairs. Although there are still hangars left today, thousands have been demolished since the 1980s. The city of Montreal still has a subsidy program for owners wishing to destroy these hangars. For more details, please consult the Regulation respecting the subsidy for the demolition of accessory buildings [03-008] at the following address:

It is difficult to conjecture how men came to know and use iron; for it is unbelievable that they would have thought of themselves to take the material from the mine and give it the necessary preparations to melt it before knowing what would result. (JJ Rousseau, Discourse on the origin and foundations of inequality among men, 1754)

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26; its specific gravity is 7.874, it fuses at 1529 degrees C and boils at 2450 degrees C. Native (pure) iron is extremely rare in nature. The earth's crust contains 4.7% in the form of oxides and carbonates. (Documenta Geigy, Scientific tables. 7th ed. 1972)

Ironwork is the art and also the technique of working iron in the forge with different tools, from stamps to hammers. These have multiple heads: round heads (unblocker), cross heads, flat heads (flatteners). The introduction of rocking hammers and those with long tips (stretchers), and in 1841 that of drop hammers mark a significant change for iron working. Before these there were multiple forging pliers, also called pincers, which are distinguished by the shape of their jaws. We must also mention the vice and the anvil, the rounded end of which, called the bigorne, facilitates the formation of the rings. Additional tools for working with cold iron are chisels, scissors and files. The tools required vary of course depending on the order of magnitude of the materials being processed.

Wrought iron is ready for all kinds of sauces. Among the smallest items, nails, keys and their locks should be mentioned. Among the major works, naval anchors and cannons occupy a particular place from a historical and technological point of view. These two extremes eloquently demonstrate the multiple uses of wrought iron.

Today, the use of iron has become popular. The exterior and interior works are mainly concentrated on private properties. More and more ironworkers are using software specialized in assisted drawing. These new IT tools allow them to easily present, modify and edit projects from a library of existing models, saving them valuable time in the planning phase. They can easily have access, thanks to the computer, to a large choice of patterns and ornaments to personalize the product according to the customer's wishes.

- Steel: Alloy of iron and carbon (0.5% to 2%). This is the key element for its mechanical properties

- Bronze : Yellow-green alloy of copper and tin

- Coal : Coal is a generic term that refers to sedimentary rocks of biochemical origin and rich in carbon.

- Charcoal : Material obtained by carbonizing wood in a controlled manner in the absence of oxygen. The process allows wood to be removed, its humidity

- Coke: fuel resulting from the distillation of different coals.

- Cast iron: alloy of iron and carbon (2 to 7%), it is obtained by the melting and reduction of iron ore in a blast furnace in the presence of carbon.

- Soft iron: Cast iron refined by the almost complete elimination of carbon (residual less than 0.1%)

- Galvanization: Process aimed at applying a layer of zinc to the metal surface. Consult our Galvanizing section to find out more.

- Pig: Large-sized primary cast iron ingot

- Coal: Solid fuel resulting from the fossilization of plants over geological time, and which occurs in deposits

- Magnifying glass: Soft iron ingot weighing 3 to 5 kg obtained using a low furnace.

- Fox: Iron ingot ready to be transformed for market needs into flat iron, round iron, strong rectangular bar, etc.

- Guardrail: Set of elements forming a protective barrier placed around the perimeter of a balcony, a landing, a terrace located on a roof or a mezzanine. The height of the guardrail and the spacing between the bars are governed by the National Building Code.

- Juliette: Type of guardrail found in front of doors where there is no balcony.

- Stringer: Support piece that allows you to hold the steps of the stairs. For iron stairs, the 2 stringers and the support post form the support structure of the staircase.

- Banister: Bars which are placed at support height on the stringers of a staircase. There are different shapes: straight bars, arcades, English style, flowers, etc.

- Handrail: Upper part of the guardrail or ramp on which we place our.

- Step: On a staircase, horizontal surface on which one places one's foot. It can be straight when rectangular or angled when the two ends have different widths.

- Riser: In a staircase, vertical part between two steps, the majority of exterior staircases do not contain one.

- Protective grille: Grille made up of several vertical bars spaced approximately 12 cm apart and welded to horizontal bars which are themselves fixed in the wall and sealed in the frame of a window or glass door. It is generally used to secure a building. Other names used: security grille, defense grille, window grille, door grille.

- Marquise: Glass awning generally located in front of an entrance door. Although in Montreal, it is rare to see glass awnings, we still call wrought iron entrance awnings “marquise”.

- Ares, Jose Antonio

Wrought iron techniques

Editions Eyrolles, Collection The gesture and the tool (2008) 144p. - Arthur, Éric Ross Iron: wrought iron and castings in Canada, from the seventeenth century to the present.

LaPrairie, Quebec: Éditions M. Broquet c1985 242p.

Available: UdM Layout rating: (HD 9524 C32 A7812) - Bouchard, R

Saint-Rémi de Napierville: the wrought iron crosses of the cemetery.

Quebec, Ministry of Cultural Affairs. Heritage Department, 1979. 98 p.

Available: UdM LSH rating: (NK 8428 B68) - Burie, Myriam

220 models of metal roof ornaments: Spikes and Weathervanes

Éditions Eyrolles Collection Templates and plots - Reference series, 2007 - Capdefer, André

Gates and fence grills: 25 models of artistic ironwork Editions Eyrolles 3rd ed 2011. 56 p. - from Réaumur, R.-A

The art of converting wrought iron into steel: and the art of softening molten iron,

or to make works of molten iron as finished as wrought iron.

Paris: M.Brunet, 1722

Available: UdM LSH: microfiche - Flores, I

The art of wrought iron.33De Vecchi Éditeur, Paris, 2006 159 p - Kuhn, F

Wrought iron.

Fribourg: Book Office, 1973 120p.

Available: UdM LSH rating: (NK 8204 K84) - Mercuzot, A

Wrought iron: history, practice, objects & masterpieces.

Jean-Cyrille Godefroy: Paris, 2007 238 p.

376, St-Joseph Est, Montreal, QC H2T 1J6